Striped Socks

Yes, pirates wore stripey socks! 300 years ago, there were a lot of laws about what kind of clothes working-class people could wear. The type of fabric, the color, even the amount that went into a single garment was controlled by “sumptuary laws.” The rich didn’t want anyone to “get above their station” by dressing too nicely!

One of the few things that was not controlled was

socks. So when a pirate first came into some money, he often went out and

bought the most expensive pair of socks he could find – knee-high, brightly

colored, and often striped.

To the people of the time, it gave the same

impression as the uber-expensive hoodies worn by today’s gangsters.

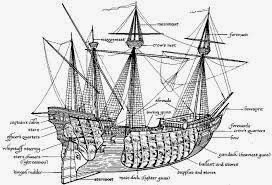

How big was a pirate ship?

Everyone imagines pirate ships as being huge,

square-masted, and carrying hundreds of guns. Movies like the Pirates of the

Caribbean franchise just enhance this image. In fact, most pirate ships were

small, nimble sloops and schooners with triangular sails.

While pirates robbed anyone they could catch, the

proper proportions between a pirate ship and a merchant vessel was the same as

between a wolf and a cow. And the pirates were just as likely to form a group

in order to attack lager prey.

The merchants handed over their goods to the

pirates for the same reason people give their money to a nervous teenager with

a knife. Anything can happen, and suddenly it becomes apparent that there are

things much more important than money.

Pirates and private property

One of the perks of being a pirate was a chance to

own some basic household goods. Unlike regular sailors, pirates owned several

changes of clothes, plates, and even silverware. The remains of sunken pirate

ships have turned up pewter dishes with the names of their owners proudly – if crudely

- engraved on them.

Often sailors on merchant ships were forced to eat

out of common buckets, using their hands.

Silk ribbons

Pirates improved the smooth wooden grips on their

pistols by wrapping them in silk ribbon. And in order to carry more than two at

a time, they tied pairs of pistols together with longer ribbons, then draped

them over their shoulders.

No one ever said it looked too feminine. Wonder

why?

Blackbeard

Although he cultivated a fearsome reputation, the

pirate Blackbeard never harmed any of his captives… In fact, the only deaths or

injuries proven to be caused by Blackbeard were during his final battle, when

he was attacked by the British Navy.

Not so privileged

Not only were pirate captains elected by their crews,

but they lacked most of the perks assumed by navy and merchant captains. In

fact, a pirate captain could not usually even count on privacy in his own

cabin. Most ships had rules stating that anyone had the right to barge into the

captain’s cabin whenever they wanted.

Tortuga

The name of the famous pirate haunt is simply the

Spanish word for “Turtle.” There are several islands by this name in the

Caribbean. Some were named because their shape looked like the dome of a turtle’s

shell, others because sea turtles laid eggs there.

Davy Jones

The name “Davy Jones” does not refer to a person,

either real or fictional. It is simply a seaman’s slang for the devil. Going to

“Davy Jones’ Locker” meant that when you died, you weren’t going to heaven.

Walking the plank

Pirates may have thrown some of their prisoners overboard,

but they never imagined making them walk the plank. It’s an entirely fictional

idea dreamed up by a penny-novelist trying to sell adventure books. But, after

pirates had read some of the stories, they began to practice the ritual. They’d

read it in a book; it must be true.

Saucy Sadie

A female river-pirate named Sadie the Goat (for

her habit of head-butting her opponents in a fight) got into a scuffle with an

equally tough lady, a six-foot-tall bouncer named Gallius Mag. Mag won the

fight by biting Sadie’s ear off, and kept the ear as a souvenir.

Years later, the women met again and became

friends. Mag gave Sadie the ear back, and Sadie wore it on a chain around her

neck for the rest of her life.