What words call up a more vivid picture of

treasure and adventure? The giant ship, laden with gold, just waiting for

pirates capture her and make their fortune. But what is a galleon, anyway?

Very simply, it was a type of ship. In the modern

world, we don’t see much difference between different types of ship, But the

galleon is easy to identify.

Sailing ships have changed over the years, in much

the same way as cars develop, and for very similar reasons. Money drives a need for better technology.

The famous galleon developed

from the carrack. This was a very

primitive type of ship, based on the idea that a sailing vessel should be

shaped like a half-moon. The bottom was rounded, the sides bowed out, and the

front and back of the ship were sharply raised. By putting all the weight in

the center of the ship, and raising the bow and stern, builders created a

vessel that was very hard to sink. It was also hard to steer, and did not move

very fast.

Columbus’s Santa Maria was

a carrack. It took her 10 weeks to cross the Atlantic.

The galleon was an early effort at scientific ship-building.

It was not a ship based on theory, but on practical application. Pedro Menéndez

de Avilés and Álvaro de Bazán, captains in the Spanish Navy, were credited with

the actual invention of the galleon at about 1550. They wanted a ship that

worked for long sea voyages.

Like the carrack, the galleon had a very raised

stern, sometimes four or five stories above sea level. This gave a raised

platform for the officers to oversee the work of the ship, and provided

comfortable living quarters for the gentlemen. Often the stern of the ship was

richly decorated. Galleons were often named after saints, and the image of the

saint was painted across the massive stern of the ship. The vessels were

brightly colored, and detailed in real gold leaf. Sometimes even the sails were

painted, two favorite themes being a large red cross, or Spain’s coat-of-arms.

The front of the ship was much less raised, the

sides were nearly straight and much more streamlined. It was a ship made to

sail long distances. Magellan used it on his voyage around the world, and

Francis Drake used another - The Golden Hind - on his voyage. Drake took some time out on his trip

to stop by a Spanish settlement, where he used the firepower of his galleon to seize

a smaller Spanish ship, capturing so much gold that he needed 6 days to move

the treasure onto his ship.

When he made

it back to England in 1580, he paid back his investors at a rate of 4,700%,

giving Queen Elizabeth I so much money that she was able to pay off the

national debt with it. She knighted him, which proves that piracy does pay.

Galleons quickly superseded the carrack as

warships (One Portuguese galleon was said to carry 360 cannons.) but they were

also large enough to act as transports, and some were refitted several times as

they alternated between the two tasks.

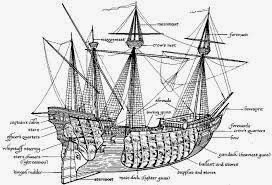

The galleon became the prototype of the “fully

rigged ship.” It usually had three masts. The front two masts had two square

sails each, one above the other. The last mast had a triangular sail hung from

a slanted crosstree, a rig which is called a “lanteen rig.” In addition, the

front of the ship had a prominent “nose,” called a bowsprit, where another

square sail was hung.

The rigging, or rope-work, on the ships was becoming more complex as well. During the long sea voyages, it was not uncommon

for most of the crew to die, either from malnutrition, thirst, or from exotic

diseases. Left with a crew too small to work

the ship as it was designed, the sailors were forced to invent new ways to move

and secure the sails. Once invented, these methods spread to other ships.

The English modified the ship’s design for their

own uses. John Hawkins, an English captain, developed a longer, lower “race

built” galleon that was faster and more maneuverable. When the Spanish Armada

attacked England in 1588, both sides were sailing galleons. In that

confrontation, the English forces used fire-ships to scatter the armada (which

is the Spanish word for ‘fleet’), which then met with severe storms that

scattered it farther and drove many ships aground.

The loss of their armada was devastating to Spain.

Each of their 130 ships had required months of work by hundreds of highly

specialized craftsmen, and many specialized materials. The keel was made of

oak, the masts from pine, the decks and fittings of other hardwoods. Building

the Armada destroyed the forests of Spain, which have never recovered.

But Spain still had the gold and silver from its

New World colonies, and galleons – large and heavily armed – continued in use.

Carracks had long sense been consigned to use as cargo ships, but heavily armed

galleons could haul cargoes of gold. Ship technology continued to march

forward. New ships were being invented all the time. Schooners, barques,

barquentines, fluyts, were faster and more maneuverable. The Spanish, however, were not stupid. Their

treasure ships traveled in fleets.

After the age of the buccaneers, when men like

Drake used government money to obtain galleons of their own, which they used for

piracy (based on the concept that if you were on the other side of the world

and no one could catch you, anything was okay.) no pirate every robbed a

galleon.

If you want to see a

galleon, you need look no farther than Roman Polanski’s 1986 movie, Pirates! Though the movie only earned a

25% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, it has been praised for its acting. A full-scale

galleon was built for the movie, a replica of the 17th century

Spanish Galleon Neptune. Above the

waterline, the boat is nearly perfect, but below the waterline it had a steel

superstructute and a 400 horsepower engine. The ship played the part Captain

Hook’s Jolly Roger in a made-for-TV

series, Neverland. You can see the

ship today, if you go to Genoa Italy, where it is on display for a 5 Euro fee.

Nice informative post but I have to point out a term that you misspelled -- lateen. It's not lanteen. It was found in this sentence: The last mast had a triangular sail hung from a slanted crosstree, a rig which is called a “lanteen rig.” In addition, the front of the ship had a prominent “nose,” called a bowsprit, where another square sail was hung.

ReplyDelete