There’s no doubt that pirates are beloved at this point in

history. We are losing the image of pirates as berserk, bloodthirsty, mindless

criminals and beginning to pick up the notion of pirates as individuals, revolutionaries,

freedom fighters.

But there is even more to the notion of pirating than that.

I want to talk for a moment about the sheer guts it took to become a pirate and

live a free life.

First was decision to become a pirate. Many times this came

during a pirate raid, when browbeaten, overworked, poorly fed sailors

encountered pirates – men who ate what they liked, drank what they liked, and did

what they liked. The hearty call to “Join us, and become free men!” was the incentive

that moved many a sailor to “go on the account”.

But other circumstances drove men to become pirates.

Sometimes the sailors rebelled, and became pirates on their own. This was an

act of supreme courage. To leave everything you have known, on the bare feeling

that there must be something better. My researches indicate, moreover, that the

prime motivator in many of these actions was not one pertinent to survival.

Instead, it was a matter of dignity. An elderly member of

the crew was beaten. The captain had simply been too high-handed. Pay was held

back. Whatever it was, the ship’s employees simply had enough. Rising up

against an employer carried the death penalty, and yet they did it anyway.

It’s interesting to note that, during the Golden Age,

pirates organized their ships the same way. I have seen no instance of

variation (except for Steed Bonnet, who was certifiably insane) Everyone in the

crew received a fair share of the profits. Officers, who had more skills and

took more responsibility, were paid more. But not that much more. A captain

never made more than twice as much as the average run-of-the-mill pirate. It was, in short, a socialist revolution.

After all, does anyone actually work twice as hard as anyone

else? And in a world (the pirate ship) where everyone’s necessities re met, how

much more does anyone need?

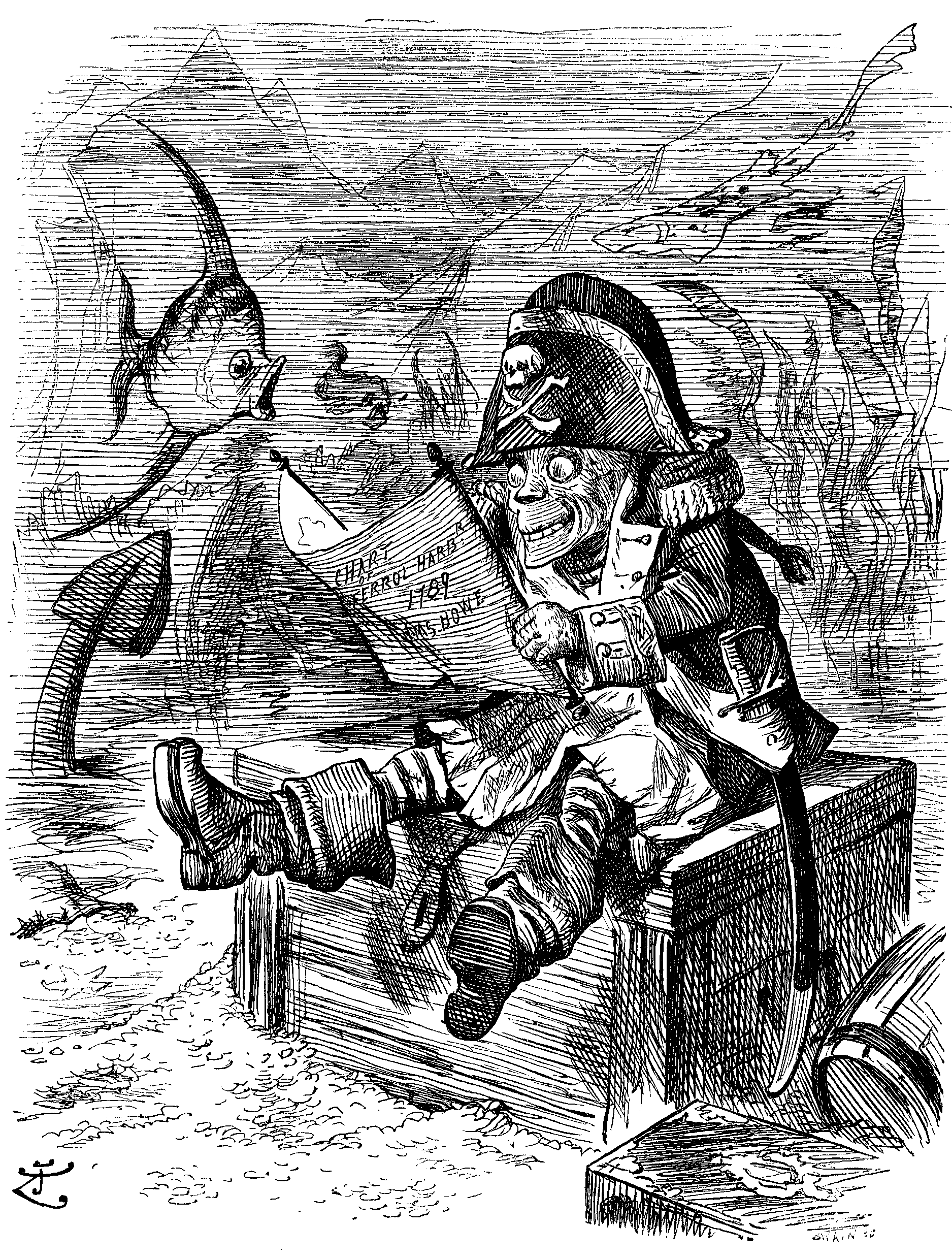

Pirate captains lived high. Their double-share of plunder

made them enviable figures. In the eyes of townsfolk and common sailors, these

men were rich. Yet their share did not prevent their crews from being well-off

in the extreme.

It’s also notable that folk kidnapped by pirates often

became pirates. The most famous instance of this is Bartholomew Roberts.

Kidnapped from a merchant ship for his navigational skills, Roberts quickly joined

the pirate crew in spirit as well as fact, and became captain within only a few

months. Roberts was one of the strongest proponents of piratical behavior. His

observations are notable because he spoke of the freedom given to formerly

upper-class individuals by the pirate lifestyle. One man did not have to carry

too much responsibility. That weight could be shared by all, to the benefit of

all.

Once in control of a ship, pirated did what they pleased. Very often this involved some very intrepid traveling. I’ll confess, I was hooked when Captain Jack Sparrow said, “Bring me that horizon!” Many actual pirates had the same attitude. Henry Avery started out in a Spanish port, sailed around the tip of Africa to get to the Indian Ocean, where he raided shipping. When he had his fortune, he crossed the Atlantic to the Bahamas in order to cash in his ill-gotten gains. Then – according to legend – he then re-crossed the Atlantic to get back to England and retire.

Not bad for a man sailing a ship only 100 feet long, with

only the most primitive forms of navigation. (A reliable way of calculating a

ship’s longitude would not be discovered for nearly 100 years.)

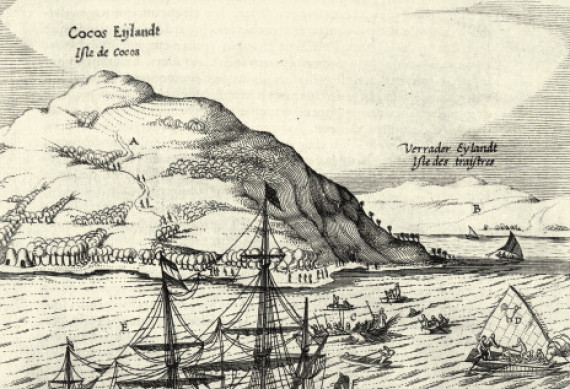

Pirate regularly crossed the Atlantic, sailed up the coast

of North America, or down the coast of South America, just because it pleased

them to do so. They did this despite the fact that they had no secure

supply-lines. Anyplace they went had the possibility to be hostile – sometimes very

hostile. And, unlike exploration expeditions funded by governments, they had no

power behind them to back them up. No funds to draw on besides what they took with

their own strength. No sure allies waited for them.

When trying to describe a place that is remote and exotic –

even in today’s hyper-connected world, the name Madagascar often turns up. To

us, it is an exotic locale. To the pirate of 300 years ago, it was a retirement

community. They had taken it, and made it their own because they wanted to.

What could be more attractive? A life where all

responsibility was shared, where all men were brothers, where every one’s needs

were met so well that plunder could be kept in an unlocked room. No one needed

to steal it because everyone had enough.

So raise a toast to the pirate life! And I’d urge you, too,

to be a little daring. Step out of your comfort zone from time to time. Be

brave. Those pirates of 300 years ago did it, and they became legends.

:origin()/pre02/24e6/th/pre/i/2009/245/f/6/piarte_angel_by_drakator.jpg)