One of the great

hardships for all Europeans in the Caribbean area during the Golden Age of

Piracy was the threat of disease. Europe’s cooler climate meant that the

colonists had no inherited immunity to tropical diseases.

They did have immunity to

an impressive list of European diseases – some of which decimated the native population

of the New World. But that is a story for another time. Today we are looking at

the dreaded Yellow Fever.

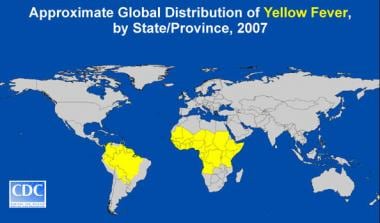

Yellow Fever was a

disease that was brought to the Caribbean. It’s an African disease, carried by

African mosquitoes. But Europeans brought African slaves to the region, and

along with them came Yellow Fever.

Nowadays, when someone

gets severely sick, one of the first questions we ask is “What do they have?” In the 17th and 18th

centuries, this was impossible. Germs and viruses were completely unknown. Disease

was blamed on “bad air,” “bad water,” or occasionally on the constitution of

the patient himself. Today we know that the disease called Yellow Fever is a

blood-borne virus, carried in the saliva of infected female mosquitoes, and transferred

to the host during a bite. The virus grows for 3-6 days in the lymph glands,

and later attacks the liver. Back in the 17th century, people only knew that the victim was sick.

The first symptoms are sudden

onset of fever, chills, severe headache, back pain, general body aches, nausea,

and vomiting, fatigue, and weakness. Unfortunately,

these are also the symptoms of many other diseases. For most people, these symptoms

are all they experience. However, for a small percentage, the symptoms become

much worse.

In these people, the

virus goes on to cause internal bleeding, kidney failure, and liver damage. The

first two gave rise to the most common names used by pirates and their contemporaries…

Black vomit. The more polite term of Yellow Fever came in 1744, when it was

noticed that many victims turned yellow. (This was the result of liver damage,

something that was not understood at the time.)

If this seems overly

horrible, remember that there were no real official names for diseases at the

time. Sickness was known only by its symptoms. And the symptoms of Yellow Fever, with its two varieties, was more confusing than most.

Worse still was the fact

that the victim, having passed the flue-like early stage, felt that he was

getting better. Such people got up and began to go about their daily activities

– often to suddenly collapse and die of horrible symptoms while outside the

home, perhaps even in the middle of the street.

Because Yellow Fever in

the Caribbean and South America was directly caused by the importation of

slaves, it almost seems like a punishment for inhumane treatment of one’s

fellow man. While I don’t actually belie in divine retribution, it is ironic

that the forced importation of Africans first caused the disease, and then the

disease cause the importation of yet more African slaves, in a cycle of death.

Yellow Fever was epidemic

in Africa, and because of this, Africans almost always suffered the milder form

of the disease. Those prone to the more lethal form had died early, and did not

have a good chance to pass on their genes. By the time the slave trade to the Caribbean began, some Africans even had inherited immunity

from mothers or other close family.

But Europeans had no

immunity, and because of this tended to get the more deadly form of the disease, which

kills 50% of those affected. The New World was home to many “bond servants” of

European ancestry, but work in sugar cane fields exposed them to mosquitoes that

carried the virus, and they died (along with their owners) in droves. Because

of this, African slaves became the preferred form of forced labor. And each new

shipment from West Africa had the potential to bring along a slightly new

strain of the disease.

The first confirmed

outbreak of the disease was on the island of Barbados in 1647. Another outbreak

occurred on the Yucatan Peninsula in 1648, and Brazil suffered from the disease

in 1685. And it was not confined to the tropics for long. As early as 1688 an

outbreak occurred in New York. How many other outbreaks occurred we may never

know. The disease may have gone untreated countless times, or have been treated

by local midwives or barber-surgeons who did not write about what happened.

Early treatment was

whatever the locals thought might work, and ranged from herbs, to bleeding to

drinking the urine of someone who had survived the disease. The latter was the

only one which might have had some effect. Even today, there is no cure for the

disease. Only the symptoms can be treated.

Of course, today we have vaccinations.

Since Yellow Fever had such a high mortality rate, it was studied extensively

by scientists. But the fact that the

source of infection was mosquitoes, not infected humans, was not discovered

until 1900. Vaccines were developed in the 1930’s. But even today, eradication

of and protection from mosquitoes remains the primary protection against Yellow Fever.

So what has this to do with

pirates? Yellow Fever was the number-one cause of death for British military

personnel in the Caribbean for over a hundred years. In 1704, a soldier

stationed in Jamaica was 7 times more likely to die during his tour of duty

than a similar soldier in New York. Such losses cut the strength of garrisons and

reduced the effectiveness of Royal Navy ships.

So when enemies were

near, Caribbean settlements sought protection from anyone who carried weapons,

and sometimes this meant pirates. Pirates protected Jamaica from the Spanish during the 1600's,

and this relationship led to years of under-the-table dealings between

Gentlemen of Fortune and a string of shady Royal Governors.

And with less military

keeping law and order, piracy had a better chance to bloom. And a populace that

faced shorter life-spans was more likely to decide to live for the moment – and

that’s the motto of pirates: A short life, but a happy one.